THE MORRIS 1800S: A CELEBRATION

13 January 2022

It is early 1969, and you have it all; the Scott Walker hairstyle, the Paisley shirt and a Ford Cortina GT Mk. II. Yet, you are beaten by a Morris 1800 bearing an ‘S’ logo on the boot at the traffic lights. What is the world coming to?

As most readers know, BMC initiated the ADO17 project as early as 1958 as the future replacement for the medium-sized ‘Farina’ range, the first of which debuted that year. However, management eventually decided that the new model would supplant the Cambridge/Oxford range and be powered by a variant of the 1.8-litre engine developed for the MGB.

The subsequent Austin 1800 ‘Land crab’ made its bow in 1964 and became Car of The Year 1965. Alas, a combination of reliability issues and the ADO17’s unorthodox lines meant that it never enjoyed the sales that should have been its due. Much of this was due to the attitudes of Alec Issigonis, who told a journalist off the record that “I’ve always thought it a waste of time and effort to build two dozen prototypes and send them all over the world on proving trials”. Alas, many other companies took a different approach.

A badge-engineered Morris followed in 1966, but by the time of the Wolseley 18/85 flagship in 1967, Car magazine observed, “ ‘how long BMC can allow the 1800’s shortcomings to prevent it from realising a truly tremendous potential is something for them to decide”. The Mk. II of May 1968 was intended to overcome the Landcrab’s issues, and before the year was out, buyers were also offered an ‘S’ version.

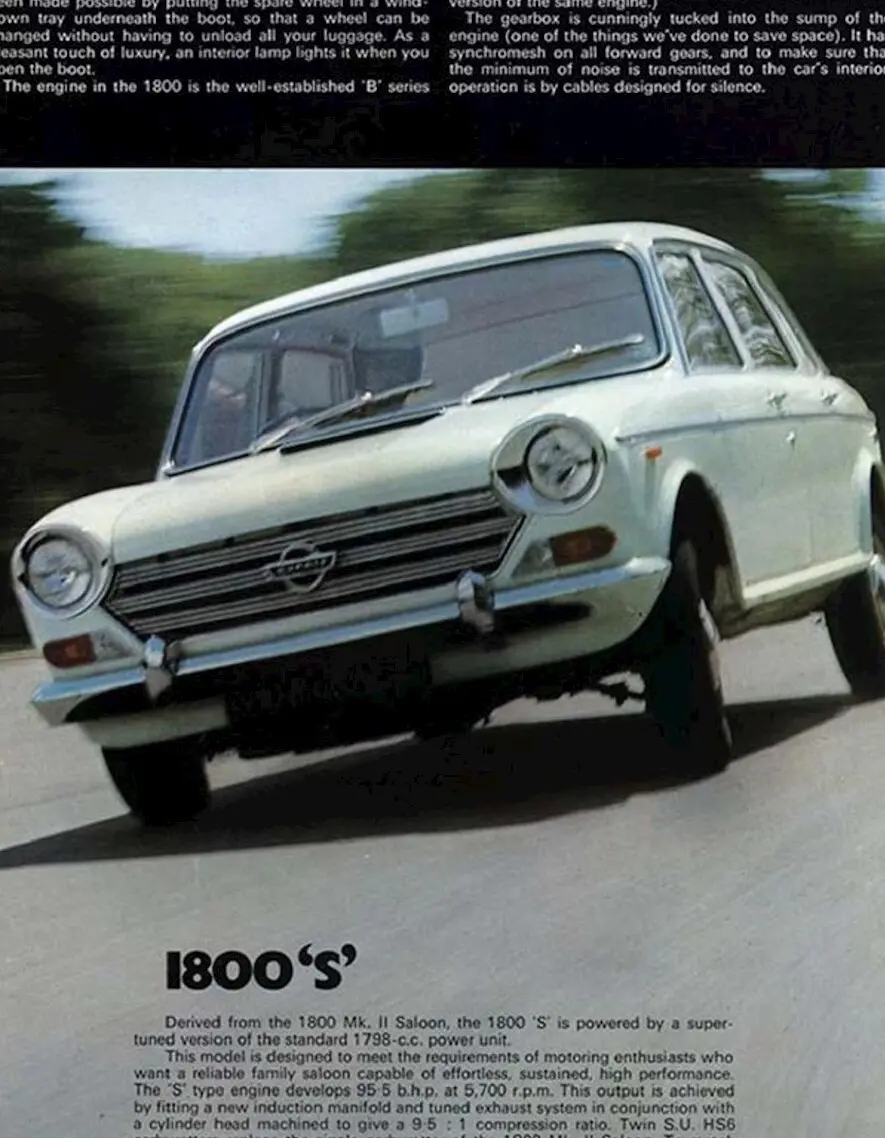

And the new Morris 1800S – corporate politics dictated there would not be an Austin or a Wolseley equivalent until 1969 – was a rather intriguing vehicle. Its main sales feature was the cylinder head created by Daniel Richmond of Downton Engineering, which resulted in a near 100 mph top speed. Autocar mused, “What it sets out to do is to offer a fast, spacious and comfortable family saloon capable of covering very great distances easily and allowing the occupants to get out fresh and uncrumpled”.

The same report found the 1800S to be “a really remarkable car on fast, twisty roads”. Meanwhile, the chaps at Motor found the Morris to be “popular with those who wanted to borrow a quick comfortable car to get safely through bad conditions because the traction is extremely good in ice and snow”. Nor was a price of £1,119 9s 9d unreasonable by the standards of the day.

Above all, the Morris was a very unusual vehicle. Its two main British competitors were both RWD and ultra conventional. The Ford Corsair 2000 and the Vauxhall Victor 2000 FD favoured Trans Atlantic styling tropes; they could even be specified with a steering column gear change. By contrast, the Landcrab almost defiantly avoided all Detroit influences and appealed to architects, town planners, and anyone who appreciated its approach to engineering.

The Mk. III succeeded the Mk. II in 1972, and the option of a six-cylinder 2.2 litre E-Series engine meant there was no need for an ‘S’ version. Today, many enthusiasts argue that the high-performance Landcrab is somewhat of a hidden gem – and they are right.