THE HENNEY KILOWATT - THE ELECTRIC RENAULT DAUPHINE

08 September 2022

Many of you will have read of the electric 2CV Camionette made by The 2CV Shop in Top Gear magazine. But, of course, a battery-powered version of a famous French car is not a new phenomenon, for 1959 marked the debut of the remarkable Henney Kilowatt– aka a Renault Dauphine with a General Electric motor powered by lead-acid batteries.

The story commences with the US industrial magnate C. Russell Feldmann - the owner of the National Union Electric Company. The NUEC was the parent company of the Exide Battery Corporation, the vacuum cleaner maker Eureka Williams and the Henney coachbuilding firm, which produced ambulance, hearse and limousine bodies. He believed an electric car would provide excellent publicity, while the Dauphine’s rear-engine layout and light weight made it the ideal donor vehicle. It was also the second most popular imported car in the USA after the VW Beetle.

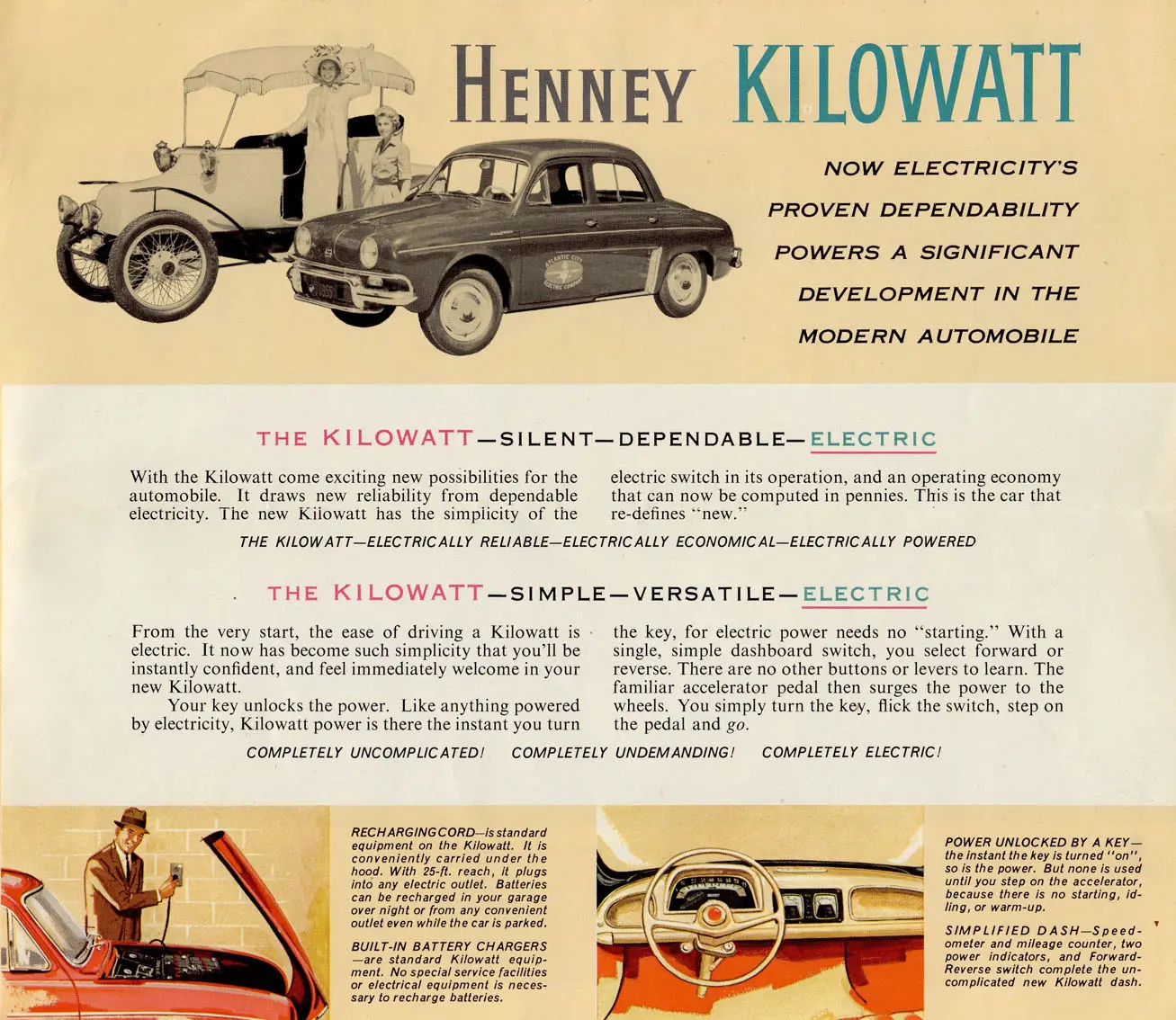

Feldmann ordered 100 Renaults sans powertrains, but his development engineer Victor Wouk had concerns about using lead-acid batteries. However, the project continued, with Henney modifying the bodywork and Eureka Williams building the electric motor. The resulting Kilowatt may have resembled a standard Dauphine but lacked a conventional transmission. Instead, the driver selected forward or reverse via a dashboard switch. The control was mounted between a voltmeter and an ammeter in the middle of the fascia.

The NUEC claimed, “You simply turn the key, flick the switch, step on the pedal and go”, although “go” was a slight exaggeration with a 35 mph top speed and a 40-mile range. The 12 6-volt batteries had a life expectancy of two years, and the standard equipment included an onboard DC charger and a 25-foot cord. Your new Kilowatt could be re-powered from any 110 or 220-volt outlet. The company initially built around 200, with sales restricted to electrical companies, but a 1960 second-generation version became available to the Great American Motorist.

Compared with early models, the power output of the latest Kilowatt was doubled from 36 to 72 volts, giving a top speed of 60 mph and a 60-miles range, and buyers could choose Montijo Red or grey paint finishes. However, at $3,600, it was nearly twice as expensive as a standard Dauphine, cost virtually as much as an Oldsmobile 98 and a heater was a $400 extra. It also lacked a boot as the electrical system occupied the front compartment. Not entirely surprisingly, the Kilowatt lasted for just two years, and of the 47 believed to have left the factory, less than 15 found a home with private buyers.

The NUEC sold the unfinished Renaults to a Florida dealer who retrofitted them with a petrol engine and sold them as new Dauphines. The term “ahead of their time” may be an appalling cliché, but it does appear that Feldmann was offering a form of 21st-century motoring at a time when tail fins and chrome denoted social prestige. Four Kilowatts are said to survive – each fulling the brochure’s promise of “exciting new possibilities for the automobile”.