Staying Positive: The CitiCar walked so Tesla could run

14 April 2023

The battle between batteries and the internal combustion engine has been waged before – at the start of the 20th century. Before certain key developments put liquid fuelled cars out in front, it looked like electric vehicles were there to stay, even in the soon-to-be-car-mad United States, which soon rediscovered its love for EVs when the Fuel Crisis bit deep.

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had much to do with the popularity of the CitiCar and Comuta-Car.

At least 4,444 of these tiny electric vehicles were produced; until the Tesla Model S, they were the US’s best-selling post-war battery-powered cars (all variants of Detroit Electric’s models managed between 12,000-25,000 units between 1907 and 1939, depending on sources).

Florida-based Sebring-Vanguard (S-V) launched the CitiCar into a maelstrom of rising gasoline prices in 1974; while its Vanguard sports coupe, unveiled a year earlier, was a failure, S-V’s late president, Bob Beaumont, knew his nation’s beloved land yachts were in trouble.

A former Chrysler dealer from Kingston, New York, Beaumont refined the design of the sports coupe into the EV-36 with Floridian design consultant, Jim Muir.

Using a tubular aluminium spaceframe as its basis, the ABS plastic-panelled CitiCar SV-36 was designed to be as light as possible, to make best use of the meagre range and power afforded by technology of the day.

Technologically speaking, little had changed from the pre-war EVs snuffed out by the march of the internal combustion engine. Six lead-acid batteries sat under the driver and passenger bench seat, powering a two and-a-half horsepower General Electric motor.

All-round leaf springs gave a jiggly ride across town; braving the freeways was ill-advised, owing to the CitiCar’s circa 30mph top speed and vestigial doors.

That said, in the grid-obsessed USA, where towns were planned around the car, the SV36’s 35-mile range was more than adequate for a good majority of buyers. The arguments are sounding familiar, aren’t they?

Give them a reason, and they will buy; where the likes of the Renault-Dauphine-based Henney Kilowatt, Westinghouse Markett and Electra-King stood no chance in the land of cheap fuel and filling stations on every corner, suddenly, in this brave new world, a cheap ($2,700) car that needed ‘no gas’ took on a new and startling relevance.

Beaumont knew all too well: he worked with Henney on the Kilowatt in 1959 and 1960, when gas-guzzling V8s were in their ascendency. 47 were sold.

As interest grew in a worsening fuel crisis, S-V began to make improvements, replacing the 36v battery pack of the SV-36 with a 48v equivalent, thus birthing the SV-48 of 1975.

With a three-and-a-half hp motor, performance improved incrementally, though bad weather, a prevailing wind or a heavy passenger would still give an SV-48 problems.

1976’s so-called Transitional CitiCar (or Hatchback Coupe, according to sources) upped the ante further: a 6.5hp motor, two more batteries and an exciting storage shelf inside the cabin. It was joined a year later by a limited-run, extended wheelbase commercial vehicle called the CitiVan.

Beaumont’s firm would soon over-stretch itself, however – by 1977, he had sold the firm to Commuter Vehicles Incorporated (CVI), whose parent firm, the General Engines Company, built industrial engines, construction equipment, and flat bed trailers.

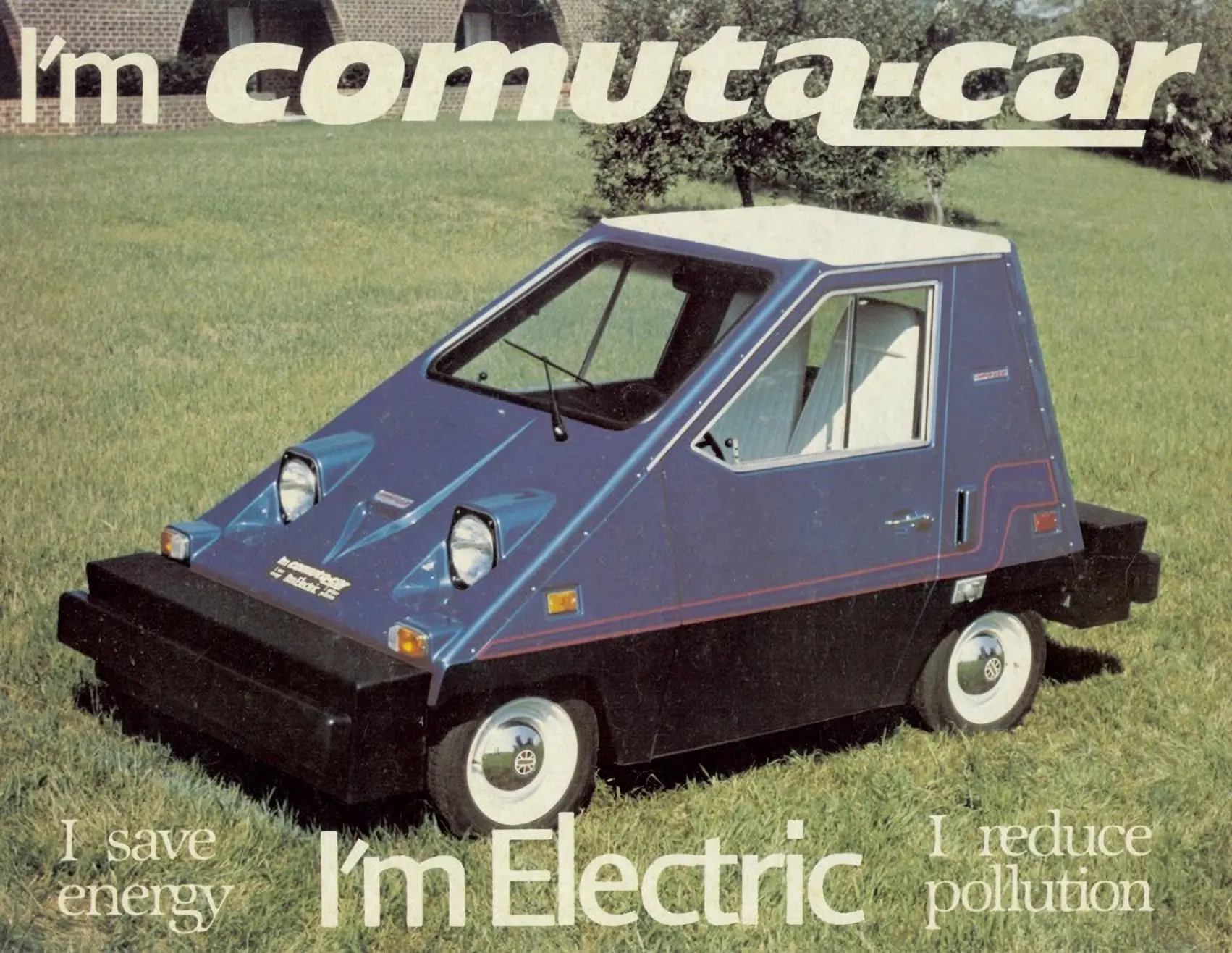

Under Beaumont, Standard-Vanguard’s Sebring Airport factory had built sold 2.300 CitiCars of all varieties. CVI used the Transitional CitiCar/Hatchback Coupe as the basis for its Comuta-Car, the next evolution of Beaumont and Muir’s design, which had put S-V into sixth place by vehicle output.

To meet Federal Department of Transport safety standards, enormous polyurethane impact-bumpers (similar to the Bayer items fitted to the MGB and MGB GT) were grafted on to the body. The rear bumper unit, now contained the battery pack; in previous CitiCars, it had remained under the bench seat.

Access to the Comuta-Car battery pack within a minute or so was handy; CVI quoted their service life around the 12,000-18,000-mile mark dependent on use.

Comuta-Car promotional material made sure to mention this new addition – lifted in concept, at least, from the post World War One era Milburn Electric models, whose battery exchange sub-assemblies worked in a similar manner.

If the World Wars were to be ignored, Milburn Electric – purchased in its entirety by General Motors in 1923 – would have placed fourth behind the CitiCar and its variants in terms of battery powered US vehicle sales after 1945; its influence was considerable, and its cars respected.

The Comuta-Car had certainly risen in expectations, too: individual, belted seats had appeared in the cabin, along with a quoted 40 mile range, a 40-43mph top speed and an overnight charge rate of around 35 to 40 cents.

Range anxiety was alleviated within literature; CVI’s research reckoned that the average US commute was 22.5 miles a day, making the Comuta-Car suitable for 70-75 per cent of driving needs.

Alongside the Comuta-Car, production of the CitiVan, now known as the Comuta-Van, continued. Both the new Comuta-Car and improved Comuta-Van launched together between 1978 and 1979; between CVI’s acquisition of S-V and the Comuta-Car’s arrival, the last CitiCars and CitiVans were assembled.

A right-hand drive variant for the United States Postal Service – the lengthened, 12hp Postal Comuta-Van – also went into production for the new decade.

Alas, the crises which propelled the CitiCar and Comuta-Car to prominence slowly waned. Gasoline cars were now smaller, leaner, and could travel further on less fuel; beset with financial issues, CVI ceased production of all Comuta-Car variants in 1982.

Liquid-fuelled cars had advanced less than their petrol-powered ancestors had done between the World Wars; Charles Kettering’s electric starter, patented in 1915, and the sheer availability (and affordability) of the Ford Model T, battered the likes of Detroit and Milburn Electric (et al) into submission.

Inter-war trading had done nothing for the price of lead and copper for motors and batteries, either.

With fewer advances to call on, buyers steadily adopted the internal combustion engine in spite of its emissions sporadic fuel availability, and difficulties in operation.

Beaumont remained an outspoken advocate of electric vehicles until his death in 2011, passing away shortly before the launch of the Tesla Model S.

Inventor, Simone Giertz, bought a Comuta-Car in 2018, naming it ‘Cheese Louise’ in honour of its wedge shaped profile. Thriving online communities for all variants of ‘C-Car’ remain dedicated to their preservation.

More than two decades earlier, with rumoured state emissions requirements threatening the sale of petrol and diesel cars, and General Motors’ Impact having made waves at motor shows, Beaumont once again tried to anticipate an EV upturn with his Renaissance Tropica.

An electric vehicle designed by CitiCar co-creator, Jim Muir, the Tropica beat GM’s EV1 (the production variant of the Impact) to production by more than a year; the EV1, built to comply with the California Air Resources Board’s Zero-Emission Vehicles programme, went on lease in Arizona and California between 1997 and 1999.

Beaumont’s Tropica was a summer fun car that sold in limited numbers owing to financial issues, while GM, across two variants, produced 1117 EV1s before recalling them to the scrapyard – a tale recounted in Chris Kline’s 2006 documentary, Who Killed The Electric Car?

If these cars had a problem, they arrived too soon into a world that was unwilling – technologically and politically – to accept electric vehicles. Though uncompetitive in range, the CitiCar, Comuta-Car, Tropica and EV1 were simply too far ahead of their time.

More than a century after those first battery powered cars, however, Tesla took the next great leap; while its Lotus Elise-based Roadster arrived to a mixed reception, its Model S was a smash hit, bringing electric vehicles into the mainstream with unprecedented levels of success.

Though the likes of the CitiCar and Comuta-Car were footnotes in the annals of automotive history, they proved the viability of battery power, a legacy that GM shied away from at the 11th hour when it sent those EV1s to the weighbridge.

The battle between battery and ICE propulsion is still being fought – and with hydrogen power in the offing, together with sustainable and synthetic fuel options, things are far from over.